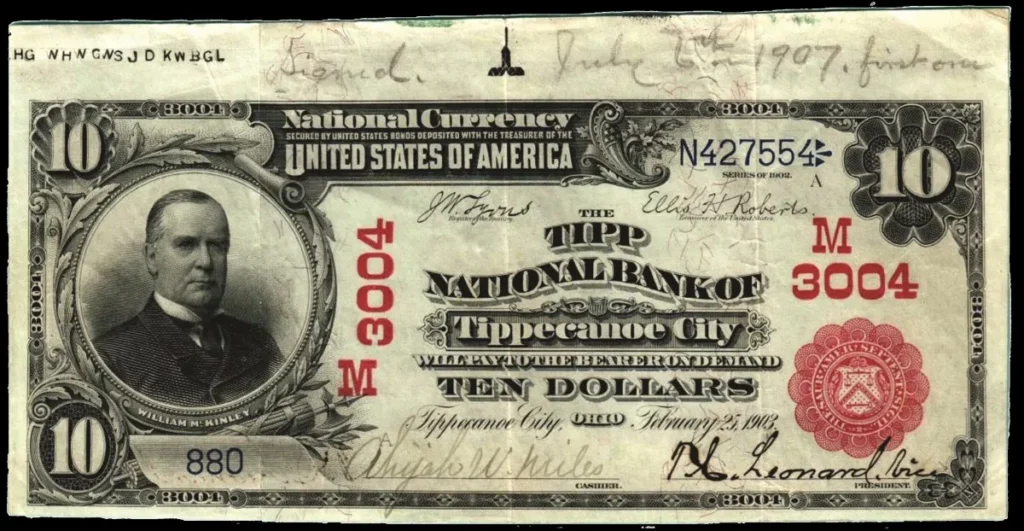

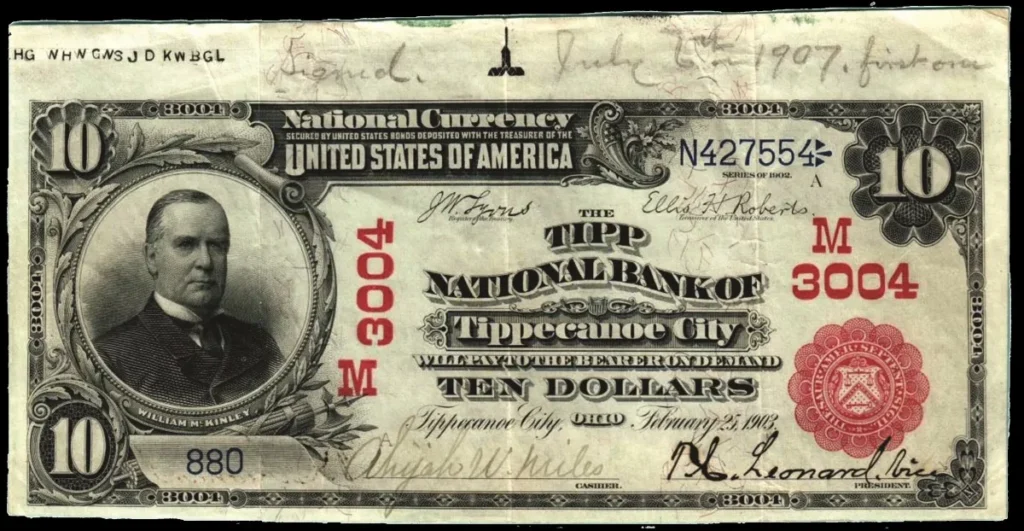

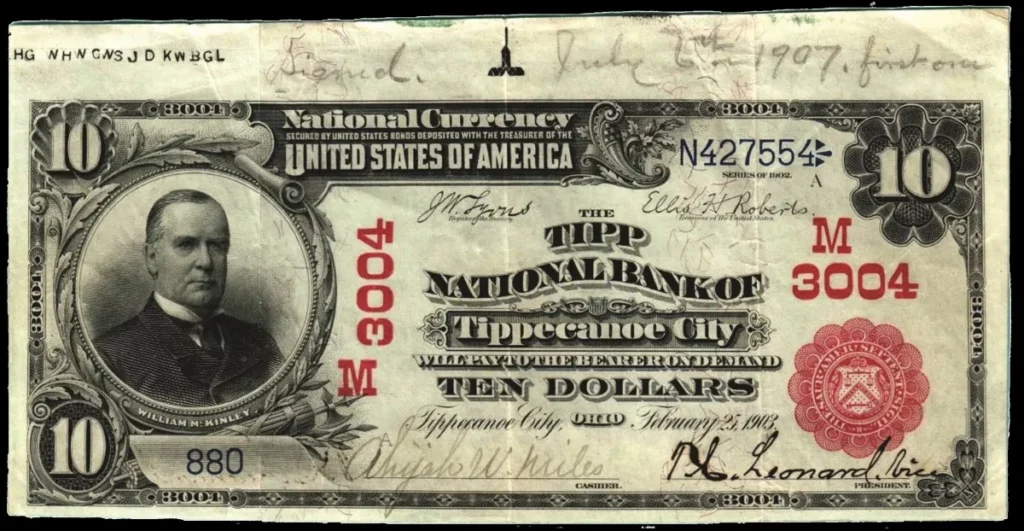

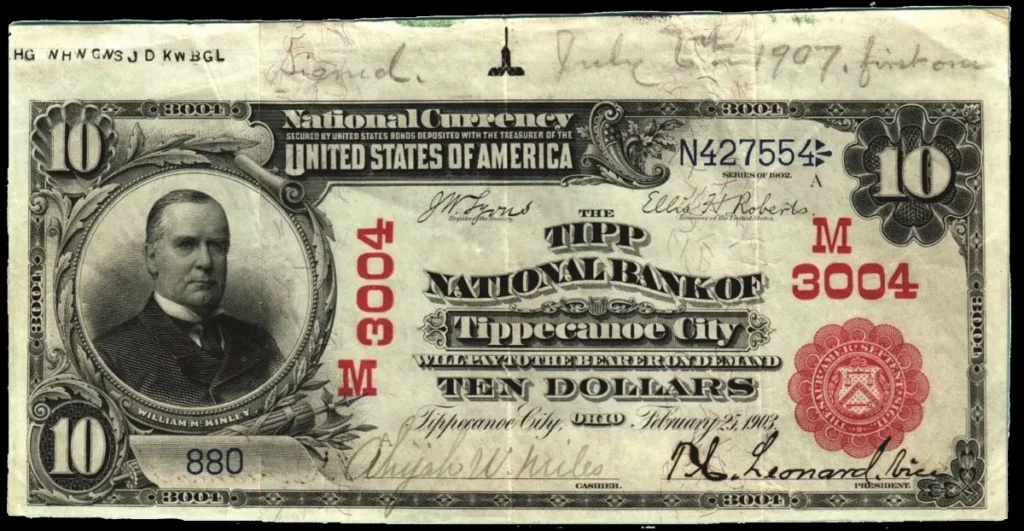

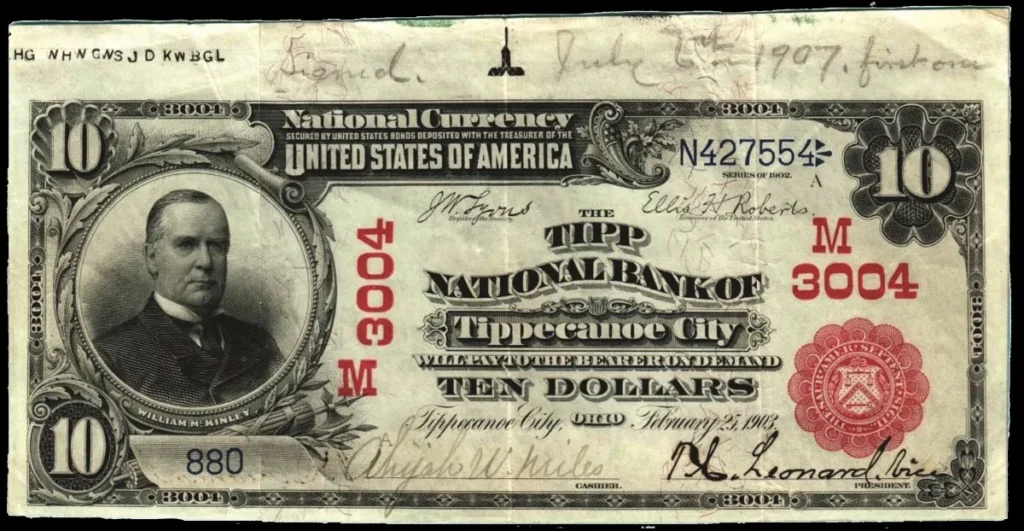

Arthur Smith presented an exquisite red seal as a contender for this space, and I was immediately captivated.

The threads woven into its fabric are numerous and intriguing; we can only speculate where they might lead us.

Let’s begin our exploration from the top, starting with the note itself.

The presence of the selvage indicates that it was preserved as a memento by one of the bankers.

Notably, penciled in the margin is the inscription “signed July 6, 1907, first one.”

A cursory examination of the bank’s officers listed in the Comptroller of the Currency’s annual reports reveals that Ahijah W. Miles served as the cashier from the bank’s inception in 1883 until 1919.

Meanwhile, Thomas Corwin Leonard assumed the presidency from 1908 to 1932. It’s evident that Leonard stepped into the role of vice president in 1907, and this note represents the first document he signed.

Although he ascended to the presidency within a year, this inaugural note remained a cherished keepsake. Such personalized touches on a national note never fail to quicken the pulse.

At that juncture, the bank boasted a modest circulation of only $25,000. Both men affixed their signatures to this sheet with utmost care and precision.

Leonard succeeded Jacob Rohrer as president. Rohrer had held the position since 1891 and happened to be Leonard’s father-in-law.

Out of all the towns in Ohio, it’s remarkable that this note survived in Tippecanoe City.

The name itself possesses a lyrical quality unmatched by most other towns across the country, let alone Ohio.

It even eclipses my previous encounters with notes from The Maiden Lane National Bank of New York.

Surely, Tippecanoe City’s name bears historical gravitas, compelling me to revisit early American history lessons I had assumed long forgotten since eighth grade.

Before delving further, let’s dispel any misconceptions about the origin of Tippecanoe’s name.

It has nothing to do with a capsized canoe. Founded in 1840 alongside the burgeoning Miami and Erie Canal, Tippecanoe City was named in honor of Presidential candidate William Henry Harrison, affectionately dubbed “Tippecanoe” for his valor at the Battle of Tippecanoe on November 7, 1811, in Indiana during his tenure as governor.

Regardless of your recollection of pre-Civil War U.S. history, one phrase undoubtedly lingers: “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too!”—arguably one of the most effective presidential slogans of all time.

It clinched the 1840 presidential election for Harrison, the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe, and secured Vice-President John Tyler for the Whig Party.

To trace the origin of the term “Tippecanoe” and the battle itself, we must venture beyond Ohio’s borders to Indiana.

The name “Tippecanoe” derives from a river in north-central Indiana near the site of the eponymous battle.

It’s an anglicized rendition of a Miami tribal term signifying “place of the succor fish people,” owing to the abundance of succor, or buffalo fish, in the local waterways.

As for the Battle of Tippecanoe, an excerpt from an account by the American Battlefield Trust provides a vivid retelling:

“In Indiana, on November 7, 1811, the Battle of Tippecanoe erupted between American soldiers and Native American warriors along the banks of the Keth-tip-pe-can-nunk, a river in central Indiana.

Following the Treaty of Fort Wayne in 1809, which mandated Indiana tribes to cede three million acres of land to the United States government, Shawnee chief Tecumseh organized a confederation of Native American tribes to resist the influx of settlers encroaching upon their territory.

This organized resistance prompted Governor William Henry Harrison to lead approximately 1,000 soldiers and militiamen to dismantle Prophetstown, a Shawnee village devised by Tecumseh’s brother, Tenskwatawa, ‘the Prophet,’ intended as the heart of the new Native American confederacy.

Arriving on the evening of November 6, 1811, Harrison was greeted by a follower of Tenskwatawa bearing a white flag, urging a ceasefire and a parley between Harrison and Tecumseh.

Sensing a delay, Harrison agreed, positioning his force a mile from Prophetstown on a hill by Burnett Creek.

Suspicious of the ceasefire, Harrison stationed his men defensively for the night.

The front lines comprised militia, with 300 regulars on standby to reinforce if necessary.

The southern flank was guarded by Captain Spier Spencer of the Indiana Yellow Jackets, distinguished by their bright yellow overcoats.

That night, Tenskwatawa incited his followers to battle from atop Prophet’s Rock with war songs and chants, promising protection from bullets through incantations.

At dawn, Harrison’s men found themselves surrounded by Tenskwatawa’s warriors.

A diversionary attack on the northern end of the American rectangle initiated the battle, rousing the sleeping force.

A subsequent assault on the southern flank caused Spencer’s Yellow Jackets to retreat after Spencer and two lieutenants fell.

Harrison reorganized, reinforcing the southern flank with Captain David Robb and the Indiana Mounted Rifles.

Despite a fierce second wave of attacks on both flanks, Harrison’s superior numbers prevailed after two hours of combat.

Disheartened, the Native Americans retreated, leading to the abandonment of Prophetstown.

Harrison subsequently razed Prophetstown on November 8, 1811, marking the demise of Tecumseh’s dream of a Native American confederacy.”

Tippecanoe City, situated 15 miles directly north of Dayton, now boasts a population of approximately 10,000.

Yet, in the 1930s, the Postal Service renamed it Tipp City to avoid confusion with another Tippecanoe in Harrison County, Ohio, located 185 miles east.

Acknowledging Ohioans’ inclination for piety, it’s worth noting that the early city was a popular stop for boatmen on the Miami and Erie Canal.

Downtown once teemed with bars and a red-light district, remnants of which can be glimpsed in the dry canal locks east of downtown.

Established in 1883 to serve as a pillar of the burgeoning community, the Tipp National Bank preserves a slice of history with this remarkable note, offering a window into a bygone era.